Five design approaches with Renato de Fusco

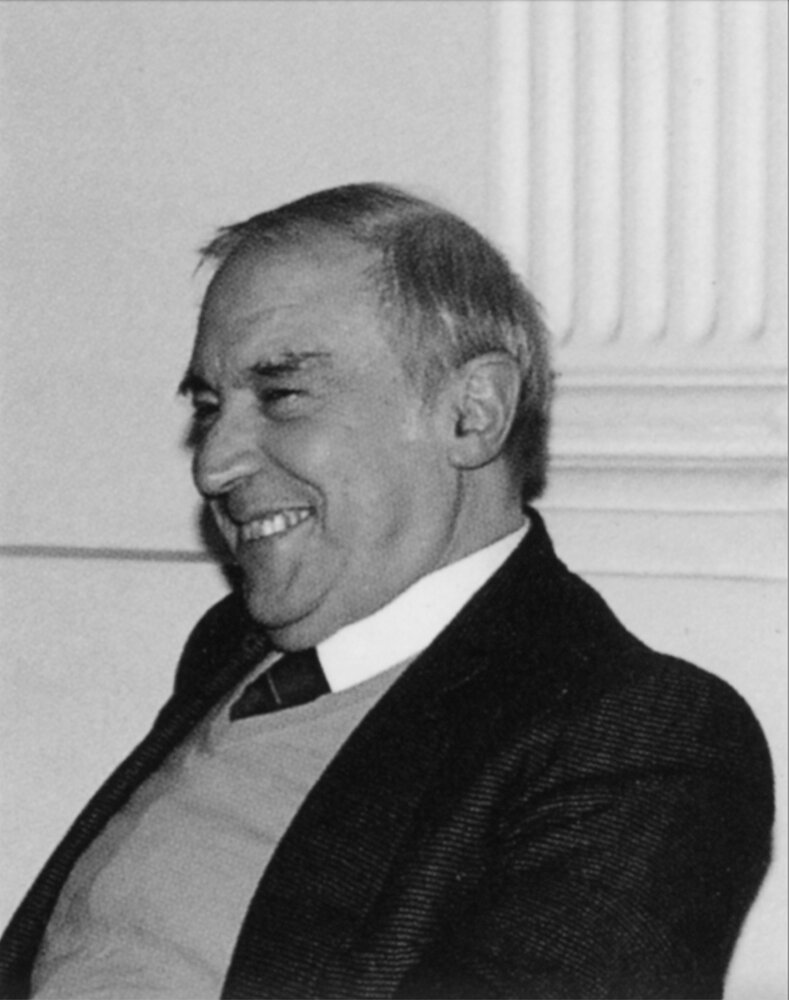

De Fusco was a prominent Italian designer recognized for his significant contribution to the field of industrial and architectural design. To commemorate his extensive and influential literary work, we have selected excerpts from an interview conducted by Francesca Rinaldi in 2011, which is found in the book History of Design .

An interview with Renato de Fusco by Francesca Rinaldi

The final hour of a March afternoon in Renato de Fusco’s studio. A sanctuary of books awaits us, the meticulous hospitality ritual by a priest of the architectural and artistic culture of these years, who is torn between chronic doubts and passionate certainties; his brow often frowned by an intuition constantly surprising us all; a paused, iterative gesture, consolidated by the methodical study that begins at dawn and concludes at night with the umpteenth book project. Always in pursuit of an idea to fall in love with and to tire himself with. With eagerness and speed, burning down phases. Because the dedication to an artwork keeps us alive; it is the reason to live.

In February 2011, De Fusco concluded a series of five meetings on design at the Palazzo delle Arti in Naples. As expected, it was a great success with the audience. He talks with us about it all, summarising themes and trends.

What has been the central idea of these conversations around design?

It all stems from the idea that design did not originate with the Industrial Revolution but rather during the Gutenberg era, that is, with the printing press and the invention of movable type. My friend and scholar Edoardo Alamaro objected that there is an excessive gap between the 15th century and the emergence of design in the 19th century. I argue that during this interval, more than a void, there was an aesthetic investigation centred on movable type, particularly in Venice, where the art of printing flourished with exquisite results. This continued until the appearance of other forms of design towards the end of the 18th century: Thonet’s production, Wedgwood ceramics, and so on.

In the history of design, there was then a conflict between the designer’s culture and the public’s culture, who did not accept that taste. Thus, the basic principle (quantity, quality and low price: a circle in which time was money and mass production guaranteed a low selling price) endured until design intervened as an aesthetic factor, or until, in any case, poorly made objects and copies of objects from the past began to be produced at low prices. The intervention of William Morris and others was a response to this degradation of design, with the idea of dignifying objects. Therefore, the design industry, in order to save quality production, found itself practicing the opposite policy: instead of many cheap replicas, it decided to produce few copies at a high cost.

From all the conclusions on this subject, which one did you feel most urgently needed to be communicated to the public?

The idea of the four-leaf clover. The book was successful (twenty reprints) and I have been susccessful myself because it was called Historia del Diseño, the first one to have the courage to use the term «history» in the title. The other trick was that I did not provide a univocal definition of design, but rather presented its phenomenology. The episode of Henry Ford is enlightening. Ford had the brilliant idea of introducing three shifts to cover the entire workday. Higher wages for workers for increased production and a greater number of items at a lower price. The assembly line. Before Ford, there was Frederick Taylor with his organisation of production in sectors. Division of labor is what allowed this evolution and, with Ford, it reached a certain level of perfection. The Model T could be everyone’s car, garnished with catchy slogans (“Any color you want, as long as it is black”) and with proper advertising promotion. The automobile enters into design only if the designer considers technical issues and not purely aesthetic ones (of silhouette and form). The real designer was Henry Ford. Therefore, the phenomenology of design is not just the four-leaf clover but the link between the four phases.

However, by directly linking the assembly line with the object of design, you do not establish a clear distinction between a design object and a generic object of serial production.

No, because in the «design» phase – as Giulio Carlo Argan also stated – the object contains a ne varietur (or precept of invariance) that must be contemplated during the stages of elaboration, until sale and consumption. Therefore, the strength of these four moments lies in their indivisibility. Extending to other topics, I venture to say that even the issue of waste comes from a project that also foresees the death of the useful object.

Over the past few years, has your perspective on throwaway consumption changed?

It hasn’t. Quite the opposite: disposable items have my full approval and embody the whole spirit of the times: functionality, a sense of economy, the reduction of effort, and the elimination of memory. Desmosine versus Mnemosine. Family inheritances are transcended. Disdain for the object: the object is no longer venerated as irreplaceable. And above all, economy. The three basic principles of design are fulfilled with disposable objects. But beware: the replacement of an object occurs not only through use but also through boredom, through weariness of the object. The durability of objects, once related to quality, is now a matter of choice. It is a mental duration: the object lasts as long as we want it to last.

The disposable object has led to a voluntarist dimension of duration.

In a society where everything is consumed and consumption is vital, the circle remains interrupted. Otherwise, it means the crisis of the entire system. And then there is a tendency to replace everything virtually, which is alien to material culture. We should reclaim materiality: the factory against the stock exchange. However, at this point, I fear that a society where everything is consumed leaves no trace of itself. How can we remedy this? We must strive for the maximum quality of disposable objects, which currently makes everything disposable. Either because of the persuasive power of advertising media or because of people’s fickleness. It is no coincidence that the cover of one of my books shows a ridiculous amount of objects that converge into a container-funnel and get lost. Perhaps the remedy is collecting. We preserve traces of the past because we find them buried by natural catastrophes or because of the intrinsic beauty of these objects that still manage to convince and fascinate us.

Is this a matter of expanding their use or of nostalgic attachment?

It is about an attachment to their form. In Rome, there is a whole mountain of preserved rubble. The design, in its ne varietur, must project not only the use and lifespan, but also the time of death. And thus include the final destination, its cemetery. Or else, incineration and recycling. The logical process of things cannot be stopped by preventing the construction of recycling plants. This is the final argument in the debate on design and industrial production. Design, as well as art, must take care of what is produced. Returning to IKEA: the unlimited consumption of objects leads to an eventual destruction of those same objects.

Is there any common ground between design and art?

Let me tell you straight away: even in art, which has made life more complicated after the appearance of photography, isms have been generated as virtual substitutes for a non-existent clientele. The difference is that, unlike in architecture or design, in art the supply exceeds the demand. Design is truly the popular art of our time.

Do you think it is foolish for a design object to arouse veneration?

Not really. It is something related to people’s emotions. When I leave home, I say goodbye to the house. I am sensitive to places, to objects. In design, however, there is an aura. To which the life that is infused upon it is then added. And it is convincing to say so: in this studio, there are objects so imbued with life they seem to be animated.

Editing books since 1991